There are many historic preservation projects involving unique structures in Saratoga Springs. A walk on Washington Street brings preservation projects of the present, and those made decades ago, into focus. Nearly every city in the Empire State has a Washington Street, named in honor of our first President. In Saratoga Springs however, it is important to remember that Gideon Putnam laid out the street plan and assigned the names, many for his children; Caroline and Phila, and in this case Washington. Underway right now, just west of the Broadway intersection, is the renewal of the Rip Van Dam and Adelphi Hotels being carried out by Thoroughbred horse owners Larry Roth and Mike Dubb. It is fascinating to see the plethora of old structures exposed from underground, and how the new construction is intermeshed to preserve and return these buildings to economic viability in the twenty-first century.

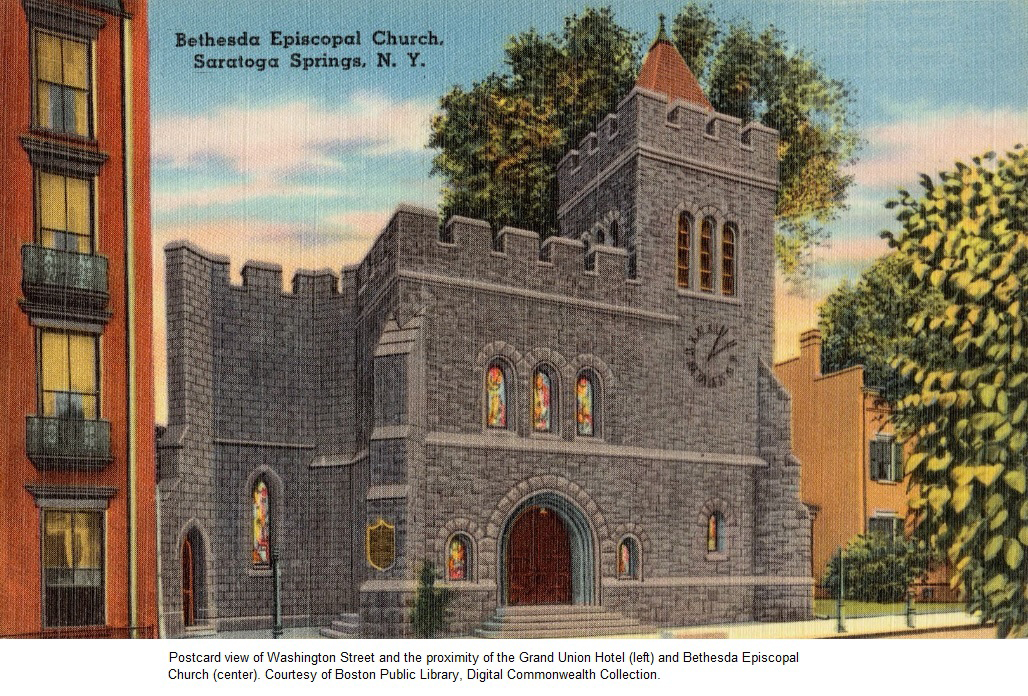

Further down the street at number 41 is the former Washburne House, a one-time cure and track-season hotel in remarkably good shape in spite of its advanced age. Across Washington Street is the masonry Bethesda Episcopal Church, which was built in a Latin cross plan in 1842. One of the oldest operational buildings in the city, it was designed by the famous ecclesiastic architect Richard Upjohn in the Gothic Revival style, one of the first churches built in America of that type. The name of the structure commemorates the miracle of the healing waters of the Bethesda Pool in Christian literature. Modifications in the late 1880s planned by Spencer Trask’s architect, Arthur Page Brown, added an impressive center archivolt with concentric moldings, which surround the revised main entrance of the edifice, and a belltower with a pyramidal shaped roof. The church was nearly surrounded by the legendary Grand Union Hotel, one of the largest hostelries in the world which sprawled down Washington Street from Broadway, and famously dominated Saratoga’s downtown.

The hotel was purchased in 1872 by Alexander T. Stewart, a New York City furniture and dry goods merchant, who happened to be the facilities’ largest creditor. Mr. Stewart also purchased a mill and the Penfield Boarding House on Washington Street for hotel expansion, and he suggested that Bethesda Church be relocated. The church members considered Mr. Stewart’s offer, and after a series of meetings and much discussion, where the voices of women were heard in an era where that seldom occurred, the church stayed put.

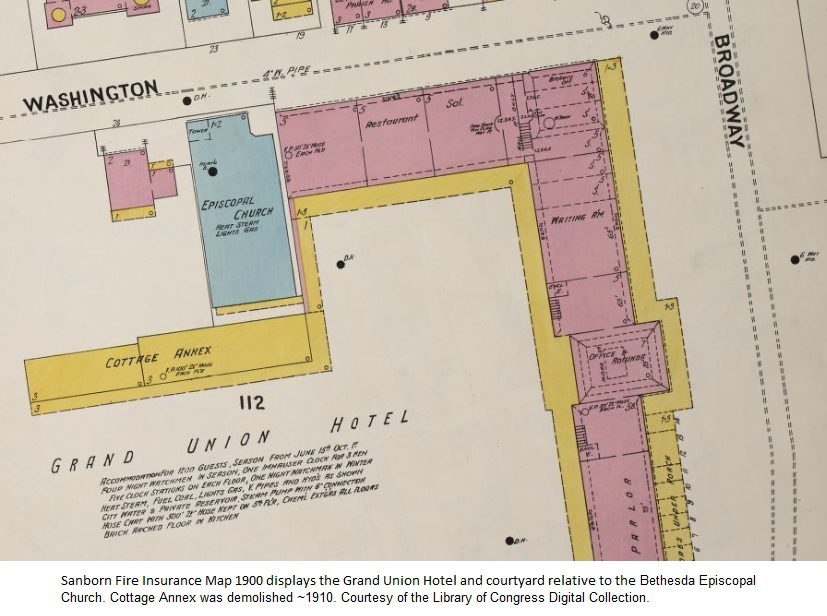

The expansion of the Grand Union and its famous courtyard was planned by architect Edward D. Harris who designed numerous Saratoga structures. The remodeling placed the walls of the immense hotel in very close proximity to the church, which limited religious functions to only the house of worship. In 1911, Katrina Trask, following the will of her late husband Spencer Trask, generously purchased and donated the Washburne House to Bethesda Episcopal Church for use as a parish house and Sunday school. It provided a remote adjunct to the church, in the only location possible at that time.

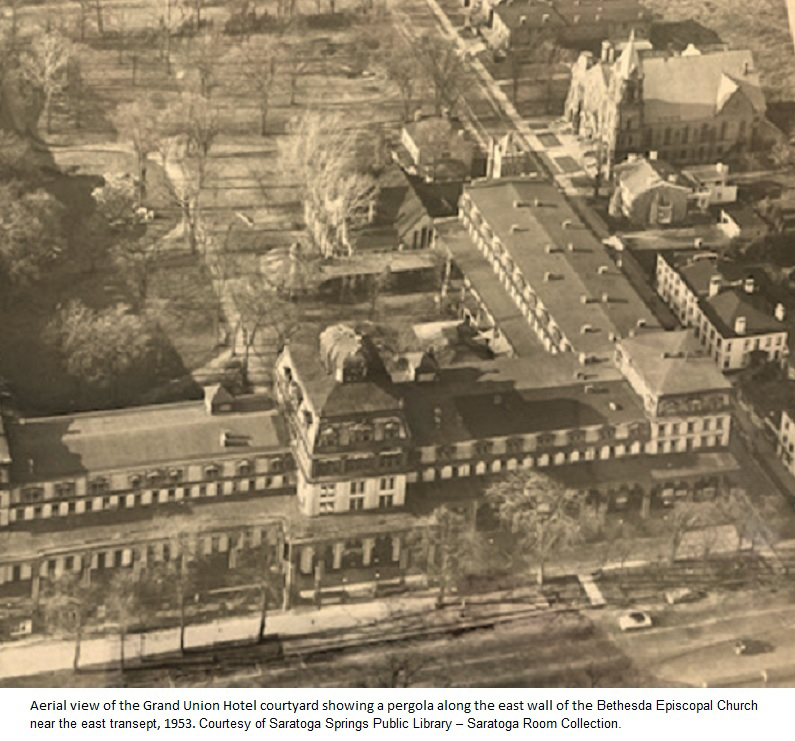

After World War II, Americans became more automobile, rather than rail oriented for vacation travel, which had a negative effect on longer term lodging facilities in Saratoga Springs. Having fallen on hard times, a final attempt to operate the Grand Union Hotel in the manner and style of its glorious past was launched in 1950 by a man from Glens Falls; Louis B. Ginsburg, under the corporate moniker the Broadway Saratoga Corporation. This entity deeded property on the west side of the Church to Bethesda Episcopal. Unfortunately, the plush dignity of the Grand Union Hotel could not survive after too much official scrutiny was paid to Saratoga’s “other” gambling operations, and after a few years of losses the Broadway Saratoga Corporation was forced to sell the unique and stately building, which would be demolished for other future use. There was an unorganized effort by local citizens to repurpose the old pile which failed to gain traction and would be labeled by the New York Times as “impotent.”

It seems improbable that the stately hotel would be replaced by a mundane commercial operation sharing the same name, which intended to build a 1950’s-era shopping plaza on the site. After the sale, the Saratogian reported on September 24, 1952:

“Officials of the Grand Union Company, food concern which has purchased the Grand Union Hotel property, were in town yesterday to confer with city officials and leaders of the Bethesda Episcopal Church, which owns adjacent land to the hotel property.”

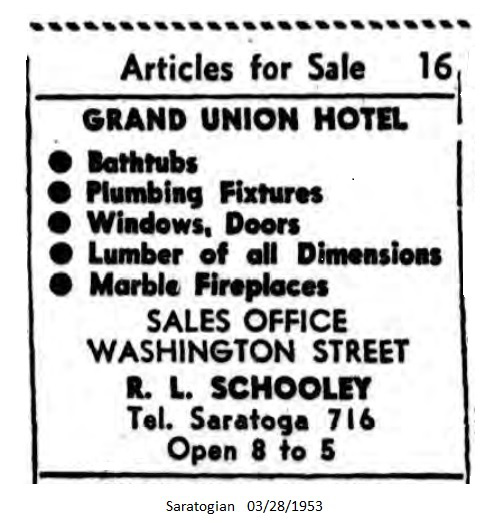

The Grand Union Hotel wreckers, contracted to Ralph L. Schooley of Auburn, with masonry saws and cables attached to bulldozers, reduced the Second Empire style building with precision. The bright side of this loss, literally, was re-illuminating the stained-glass windows of the Bethesda Church, some crafted by Tiffany, and others gifts of the benevolent Trask Family. As part of the shopping plaza planning, a right-angle wall of the former Grand Union Hotel was deeded by the new owners to Bethesda Episcopal Church and remains standing near that structure’s southeast corner. It is yet another uniquely preserved component of Saratoga Springs. The description of this surviving wall from the hotel was detailed in the Saratogian on April 17, 1953:

“The east side of the century-old Bethesda Episcopal Church was exposed to the sunlight for the first time at 10 a.m. today when R.L. Schooley, wreckers, hooked a bulldozer to one of the few remaining walls of the Grand Union Hotel and sent most of it to the ground in a cloud of dust. The Rev. Malcolm W. Eckel, pastor of the church, James A. Ryall, a vestryman, who also is the city's building inspector, and a few others were on hand. Mr. Schooley said the rest of that section of the wall will be removed later. Under provisions of the wrecking contract, a part of the wall around the southeast corner of the church will be left.”

The shopping center planned on the 6.5-acre former hotel site by the design firm of Kelly & Gruzen Architects, who specialized in military barracks and schools, calculated their project to again be in close proximity to Bethesda Episcopal Church. The former hotel walls left standing would provide a strong protective barrier. Soon after the shopping plaza opened in 1954, former mayor and local elder Clarence H. ‘Nuggy’ Knapp lamented that the new owners of the former hotel “have erected on the corners of Broadway, Washington and Congress streets, all in the name of city progress, a chain store of huge proportions. This in a measure may appease the indignation of some and alleviate the grief of others over the passing of this relic of former grandeur. When it is recalled that up to a couple of years ago there had always been a hotel of distinction on this very site since 1803 when Gideon Putnam opened his tavern there, the destruction of his monument of local history, inevitable though it was, will ever seem to many a matter of tragic consequence.”

By 1955, the church managers began incorporating the remainder of one of Saratoga’s most well-known buildings into one of its oldest. During the summer of that year the Saratogian reported:

“The church plans to extend the east sidewalk; place coping on the recently purchased Grand Union wall in order to protect the life of the wall; establish a second exit from the side of the church to facilitate evacuation in case the main exit doors are ever blocked.”

That autumn the local paper conveyed that at the church dinner-meeting this work, which incorporated something of an architectural-oddity, was complete:

“The parish has installed new sidewalks and curbing in front of the church, covered parts of the base of the old Grand Union wall with cement, placed in good condition by installing new coping on the old east and south Grand Union wall that now belongs to the parish, established a new entrance way through this wall to serve as a second emergency exit.”

Frank Sullivan, long the sage of Saratoga and a Lincoln Ave. resident in that era, would nostalgically wax poetic on the pages of the New York Times in 1959 about the lost age of “crinoline and, later, the bustle,” and of the fallen landmarks. He wrote:

“The vast hotels that once lined Broadway, the Grand Union, the United States, and Congress Hall, are gone. They gave the wide, elm-lined boulevard a unique and stately character and it would be idle to pretend that the supermarkets and one-story taxpayers which occupy their sites today are an improvement.”

Functional historic structures such as the Rip Van Dam Hotel and the buildings on Washington Street associated with Bethesda Episcopal Church are the exception rather than the rule in the Empire State, where sadly at so many locations we are left with only historic markers that announce what had once stood there. Fortunately, in Saratoga Springs the spirit of preservation is strong, and admirably resolute. So much of the past can still be viewed and touched there, due to the determined efforts of dedicated and organized individuals on behalf of preservation.