WRITTEN BY CAROL GODETTE

PHOTOS COURTESY OF WM. J BURKE AND SONS RECORDS (UNLESS NOTED)

Part one of Burke's Funeral Home.

The second part, 628 North Broadway, can be found HERE.

The three-story brick brownstone at 465 Broadway is straight out of a movie set depicting a Brooklyn exterior or a fancy residence on the Upper Eastside of NYC. The pointed arches over the tall windows and the ornate carved wooden double doors evoke a sense of elegance, warmth, and beauty. However, newer residents of Saratoga may not realize that it was the William J. Burke and Sons Funeral Home office for half of its 150-year-old existence. For forty of those years, it served as the funeral home itself.

Despite now being owned by the Adirondack Trust Company and used for their Mortgage Department, the bank still refers to 465 as the "Burke Building." This spot will always live in my mind as the funeral home's "behind the scenes" headquarters- the place my father, Richard Stone, a licensed funeral director at Burke and Sons, had his office, embalming room, and garage that housed the hearse.

But what were the beginnings of THIS SPOT?

Photo courtesy of the Saratoga Preservation Foundation

The ornate doors are one of the building's most eye-catching features.

Photo courtesy of the Saratoga Preservation Foundation.

According to Saratoga researcher Joan Walter, author of "The Land Men," three original "landmen" were granted rights to land in Saratoga in the Partition of 1772; Henry Walton owned the land on Broadway from Division Street to Rock Street, including the property 465 Broadway now stands on. The land changed hands several times from 1820 before being purchased by Dr. Samuel Pearsall in 1871.

In 1872 Pearsall built the current structure at 465 Broadway — a three-story Venetian Gothic-style brick building — he used it as a home and office. In his downstairs office, he practiced his specialty-homeopathic medicine. His patients included well-known Judge Henry Hilton, owner of the 1000-acre Woodlawn estate off North Broadway.

Pearsall also rented office space to Dr. Richard McCarty, founder of McCarty's Hospital, located in what is now Anne's Washington Inn.

I believe Pearsall set the stage for a tradition of "caring" that was the foundation of what was to follow on this spot.

After Pearsall's sudden death in 1900, his family failed to make the mortgage payments. Maria Blackmer, the wife of printer George Blackmer, purchased the building in a public auction in 1905. She owned the property a few months before selling 465 to William J. Burke Sr. in February 1906, who turned this spot into a funeral home.

Burke's career path as an "undertaker" reflected how the industry evolved.

Like most undertakers, Burke began his career in 1877 as a woodworker. In the late 1800s, most people died at home and had their services in their homes. The undertaker's job was to craft a wooden casket. Burke developed his carpentry skills with a coffin manufacturer in NYC. Then, he returned to Saratoga and began an apprenticeship with local undertaker Ebenezer Holmes.

William J. Burke Jr. and local embalmer Lyman Smith in front of Burke’s office in 1967.

Several recent magazine articles state that President Ulysses S. Grant was prepared for burial at Burke’s. Although Mr. Burke witnessed the event, Grant was embalmed at the Mount McGregor home he died at.

Ebenezer Holmes, owner of E. Holmes & Co. at 12 Church Street, was summoned by Grant's doctor to embalm Grant. However, Grant's family decided to hire well-known NYC embalmer Stephen Merritt, who arrived after Holmes had completed four hours of work on General Grant's body.

July 23, 1885, was a warm, humid day, and Holmes brought his patented "casket cooler" to keep Grant's body from quickly decomposing before his embalming was completed.

Burke had finished his internship with Holmes and ironically was employed as the house carpenter at Mount McGregor. Since Burke was still interested in the funeral industry, he assisted Mr. Holmes in preparing Grant's body for burial.

Shortly after, Burke returned to the funeral business in partnership with Ebenezer Holmes’ son, Howard, under the name "Holmes & Burke."

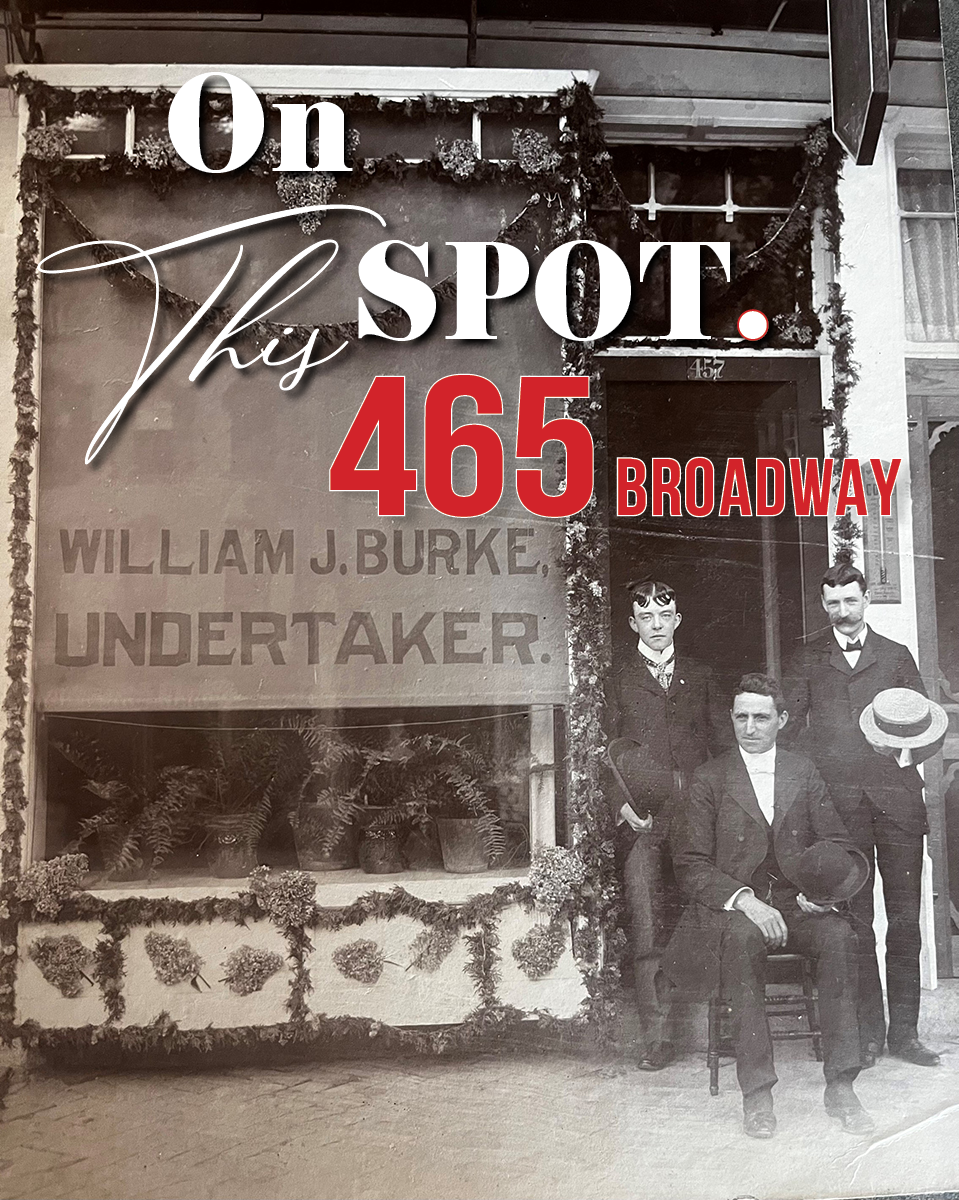

After a few years, Burke decided to open his own firm, William J. Burke, Undertaker and Embalmer, at 457 Broadway. The small storefront space was adequate since most people were embalmed and waked in their own homes. In addition, Burke was well-liked and very involved in twenty different community organizations. These core civic values have been maintained by every subsequent employee of his namesake firm.

Looking for a larger space in 1906, Burke purchased the handsome brownstone at 465 Broadway and relocated his business to the basement and part of the first floor. The Burke family lived on the second and third floors. After Burke Sr.'s death in 1930, his sons, William J. Burke Jr. and James M. Burke, carried on the family business of comforting families during their grief.

It was also where William Jr. and his wife Theresa Burke lived. As a child, I spent a great deal of time there. "Tee" watched me in her quarters upstairs if I was sick and my mother was working and unable to take care of me. As a college student, I covered the downstairs office when the staff was at a funeral.

Growing up, my friends' reactions to my father's profession ranged from looks of horror to expressions of intrigue. My father was drawn to the profession because he wanted to be a doctor but couldn't afford medical school. An 1885 newspaper describing the new U.S. custom of embalming the dead says, "An embalmer's profession is a good deal like a doctor's; he has got to understand his patient."

My siblings and I always went to our dad with any pains or ailments. Thanks to his deep understanding of anatomy, he knew to bandage us up, diagnose us, or send us to a doctor.

Rather than be embarrassed by my dad's line of work, I slowly developed pride for his often-misunderstood occupation. I silently witnessed the care, compassion, respect, and dignity my father and the entire staff at Burkes provided when people were vulnerable and broken after losing a loved one.

There were two times my father struggled to keep his composure. Both involved deaths of young adults he had led in his Bethesda Episcopal Church Youth Group. Nineteen-year-old Denton "Mogie" Crocker, a soldier in the U.S. Army, died in Vietnam in June 1966. Ken Burns interviewed his mother, Jean Marie, for his 10-part PBS documentary series, "The Vietnam War." In episode 4, Jean Marie Crocker describes "an Army captain escorting Mogie's body to Dick Stone's funeral home."

The family priest had suggested that Mogie be buried in Saratoga Springs. Instead, the Crockers chose Arlington National Cemetery.

"A corner of my heart knew," his mother remembered, "that if he were buried near us, I would want to claw the ground to retrieve the warmth of him."

The trip to Arlington Cemetery was moving and profound for my father.

My father also struggled to make sense of the Christmas Eve 1964 death of 22-year-old Penny Burnett Sullivan. She was killed from injuries in a car crash on her way to celebrate Christmas with her family in Saratoga. Penny died, but her one-year-old son and husband survived. Tears streamed down my father's face as he escorted her casket down the aisle of Bethesda Episcopal Church.

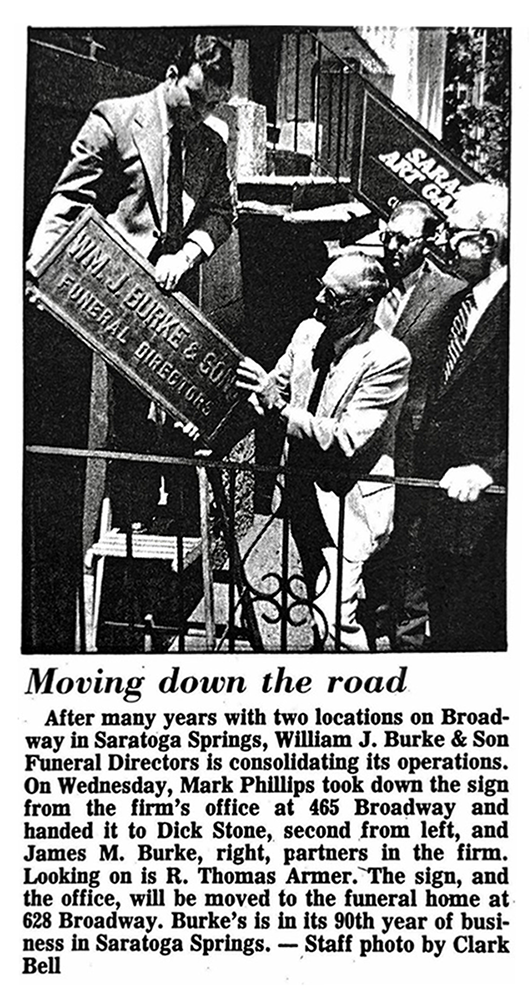

Neither William nor James had children to follow in their footsteps. Most funeral directors grow up in the family business. In 1947, my father joined the firm as an apprentice. Although my father was their employee for 23 years, he was treated as "the son they never had." After William Burke's 1972 death, James invited my father to become a full partner in the firm. My father didn't have any sons but met Mark Phillips, a fourth-generation Saratogian when Mark was a teenager cutting grass at St. Peter's Cemetery. My dad was impressed with 15-year-old Mark and invited him to start shadowing him in his free time at the funeral home. Mark began learning the trade at 465 before receiving a degree in Mortuary Sciences at Hudson Valley Community College and becoming a valued employee. It is the only full-time job Mark has ever held, even now, fifty-three years later.

One challenge in pre-cell phone and pager days was having someone answer the office phone 24 hours a day. No one wants to lose their child or parent in the night and get a busy signal or no answer when you call for help. Thus Burke's "584-5373" office line at 465 Broadway had an extension installed in our home. It was akin to the Soviet "red phone" - always manned and treated with the utmost care.

When my father was at a funeral, my college job was to phone-sit in 465's basement office, originally used as a reception room in the rare instances the deceased was not viewed at his home.

I sat at the antique roll-top desk, prepared to receive sad news upon every telephone ring. To break the monotony, I'd stroll out to the receiving room lined with wooden bookshelves filled with yellow spined National Geographics and "trade magazines," giving the room a library-like appearance. I'd browse the casket showroom, surveying the origins of "undertaking" business in the displays of wooden cherry, oak, and mahogany caskets.

In 1980, Universal Studios shot a scene for the movie Ghost Story in the embalming room. The film starred Fred Astaire, Melvin Douglas, John Houseman and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and wad filmed in various locations around Saratoga Springs. Unfortunately, this scene ended up cut from the film.

I hoped the casket companies wouldn't phone with a delivery. That meant cutting through the embalming room to open the garage on Long Alley. I tried to avoid the antiseptic embalming room. But not everyone felt the same. Universal Studios rented 465's embalming room to film a death scene in the 1980 filming of the movie "Ghost Story." Melvyn Douglas was laid out on the embalming table as a character playing a sheriff looked on. My father was disappointed to have the scene land on the cutting room floor.

This embalming room no longer exists. In June 1983, the funeral home consolidated its operations to a single location at 628 North Broadway. The Adirondack Trust, who then owned the property, tore down the garage and embalming room. The area is now a parking lot and back entrance to the Mortgage Department.

For a few years, the space on the first floor of 465 was rented out as an art gallery and as offices for lawyer Sam Aldrich. The ATC then took over the space to house their Trust Department. Today this spot continues to be a place of caring in a different sense. The Adirondack Trust cares for the interest of several home and business owners with much-needed mortgages from this spot.

Burke's legacy lived on at the funeral home's 628 North Broadway location under Mark Phillips and Thomas Armer's ownership. Last month longtime local and trusted professional Burke associates Daniel DeCelle and his son Nick DeCelle took over ownership of the 628 property.

Their story will be detailed in a future "On This Spot," documenting the rich history of this 1887 Queen Anne Victorian.

Author's note: Many thanks to Mark Phillips for his extensive historical records, Mitch Cohen for research aid, and Saratoga Preservation Foundation for their files.