{From the 2024 Spring Magazine}

Written by Bill Orzell

Saratoga Springs has inspired many types of artistic creation, and has been graced by the science of design in much of its architecture, many examples of which have survived to our time.

Pride of place has been an American ideal since before the founding of the nation, and resident examples enrich the locale. An architect who sketched out so many functional arrangements at the Spa was Charles Wellford Leavitt, who was born in Riverton, New Jersey in 1871. He was a product of the Gilded Age and the Cheltenham Military Academy near Philadelphia, graduating as a Civil Engineer. His riding skills were doubtlessly improved at the Academy whose bridle paths intersected those of the adjoining Widener Mansion and training grounds.

His first engineering tasks included railroads and water systems; in 1897 Mr. Leavitt founded a firm in New York specializing in Landscape Architecture. His equine connections established while at school led to his introduction to William C. Whitney, who was stepping away from a governmental and business career, and turning toward thoroughbred racing for relaxation. He decided to outfit his estate in Westbury, Long Island with a private training track, contracting with Charles Leavitt for the design. Subsequently the Leavitt firm was engaged to build the new Empire City racing facility near Yonkers for William H. Clark, an attorney and Corporate Council for the City of New York, reputed as the brightest mind in Tammany Hall and Wall Street. The 1899 opening of this track cemented Mr. Leavitt’s reputation for that type of work, which led to additional contracts for polo fields in Cobalt, Connecticut and Newport, Rhode Island and a steeplechase course at Gladstone, New Jersey for Charles Pfizer. The Leavitt firm also began specializing in producing extraordinary garden settings for private homes and estates.

William C. Whitney led a group of investors who purchased the Saratoga Race Course in 1900, which for the preceding decade had been mismanaged into degradation. Gottfried Walbaum, although he improved the facility with a grandstand, betting ring and clubhouse designed by H. Langford Warren soon after his 1891 purchase of the track, diluted the quality of racing. The consortium led by Mr. Whitney sought to recapture the prestige of the plant, and brought in Charles W. Leavitt for their rebuild. The physical track itself was the first order of reconstruction; it was enlarged from a one mile oval to a mile and an eighth with two starting chutes, an inner turf course added and shifted to the position we are familiar with today. Mr. Leavitt supervised the enlargement and relocation of the grandstand, as well as the betting ring and clubhouse, which were newly aligned to serve the relocated track. He added an attractive trussed rafter elliptical paddock building for saddling the entries prior to the race, which in recent decades has been remodeled into racing offices and a pari-mutuel window pavilion.

Mr. Leavitt’s design called for the planting of trees, shrubs and flowers, as he had done in the gardens of many private estates, where large trees were transplanted, creating an immediate desired effect which would have otherwise taken a lifetime if the usual nursery trees had been planted. The success Charles Leavitt achieved with the rebuilt Saratoga Track led to contracts to rebuild Bennings racetrack near Washington D.C. and to construct Belmont Park on Long Island. Subsequently he went on to plan race tracks at Rye, New York, for the Maryland Fair Circuit, across Canada in Toronto, Montreal, and Winnipeg, and in Havana, Cuba.

Charles W. Leavitt’s designs continued to be sought by those in Saratoga Springs, with one example being Richard Canfield, who wanted to complement the restaurant just added to his casino by architect Clarence Luce with al fresco dining. The New York Herald reported on May 17, 1903,

"I want," said Mr. Canfield to the landscape engineer, "the finest park that money can make, complete to the last twig, in six months. The cost is immaterial. Go ahead."

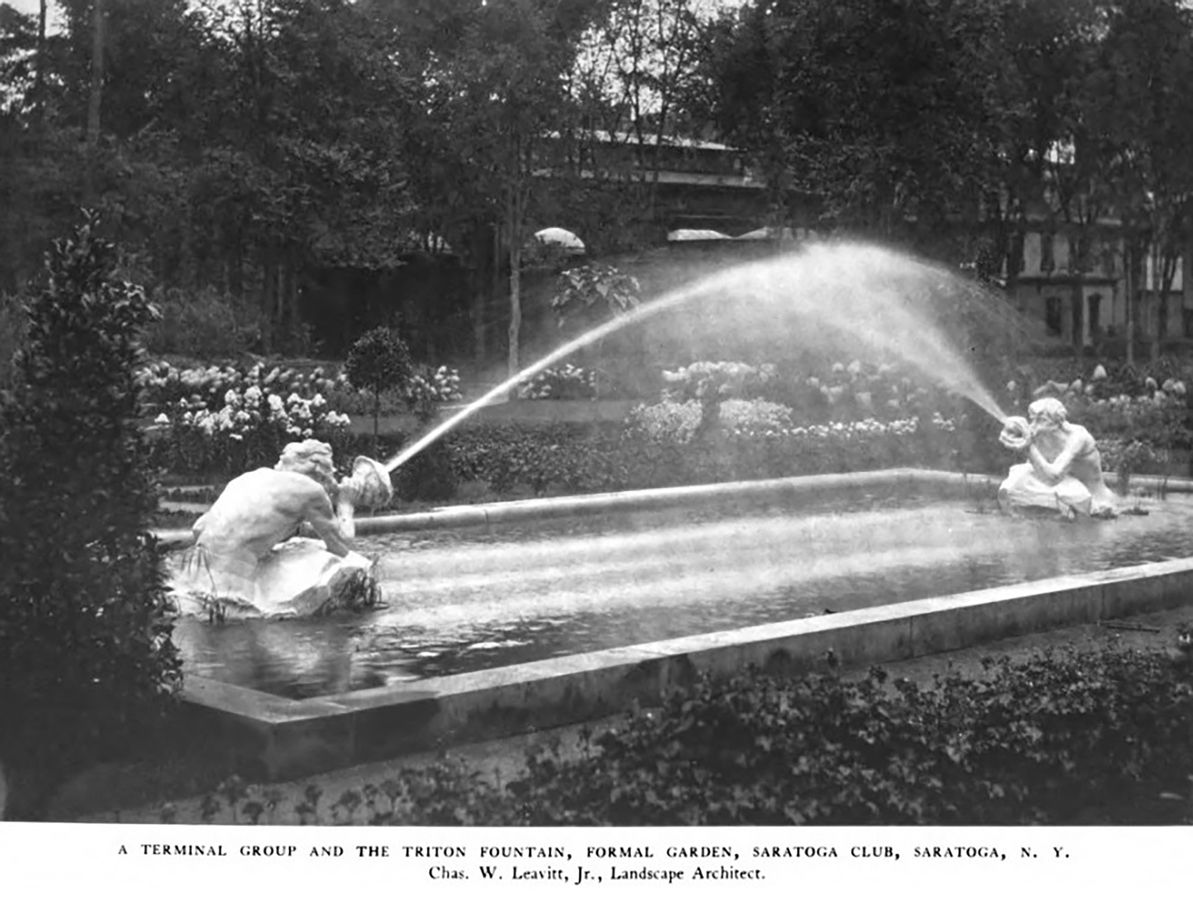

His park design included an artificial stream, the outfall of numerous springs, and tons of soil were hauled in and fashioned on the steep terrain and plateau which had formerly been known as the seasonal Indian Encampment. Extensive flora was planted along pathways to create an Italian Garden, with fountain and imaginative statuary conceived by sculptor Louis Potter, and carved from Carrara marble. Many regarded Mr. Canfield’s investment to rival Monte Carlo in style and excitement. The November 15, 1903 issue of Architecture Magazine ran a feature on the formal gardens of the Saratoga Club, credited to Charles W. Leavitt as Landscape Architect. It seems surprising that Mr. Leavitt and Louis Potter have been so long overlooked as creators of this city hallmark, especially the “Spit & Spat” Triton Fountain, until you consider the discrete nature required by Mr. Canfield’s private business.

The election of Governor Charles Evans Hughes in 1906 ushered in a reform movement which sought to abolish all forms of gaming, which he considered a disgraceful scandal. Richard Canfield, Prince of Gamblers, was the favorite target of reform prosecutors and shuttered his extensive operations in 1909, which allowed the Village of Saratoga Springs to acquire the magnificent casino and grounds in 1911 for a fraction of their value. The gambling ban which blocked horse racing during 1911-12 caused the Congress Hall Hotel to fail and default on village taxes. This longtime Saratoga hostelry was razed in 1913 and the property on which it stood was combined, along with the casino, into the expanded Congress Park.

Senator Edgar T. Brackett had begun a movement to de-commercialize the numerous mineral springs which were noticeably depleted, and the cause for a New York State Reservation to achieve this end was championed by Spencer Trask. His unfortunate demise in a rail accident while travelling on behalf of the proposed Reservation led his widow Katrina Trask to memorialize his efforts with a public monument. Mrs. Trask selected Daniel Chester French to create the Spirit of Life sculpture, Henry Bacon to design the niche and reflecting pool, and Charles W. Leavitt as Landscape Architect, for the tribute to be placed at the former Congress Hall site. Mr. French told writer Selwyn Brinton,

“This was a wonderful opportunity, because they gave us this entirely unimproved plot of ground and permitted Mr. Bacon, the architect, and Mr. Charles W. Leavitt, the landscape gardener, and myself, to treat it as we saw fit. I flatter myself that the result is a sufficient indication of this way of doing things.”

The Village of Saratoga Springs incorporated into a City in 1915, and the new municipality had a marvelous park at its urban center. A civic subscription drive, limited to a one-dollar contribution, was taken up. The fund managers contacted Charles Leavitt another time, asking him to design an entrance gate which would be a testimonial commemorating the efforts of Senator Brackett, who had launched the local preservation movement. Two principal granite piers, surmounted by decorative lamps, form the gateway with two subordinate piers, all of which are connected by ornamental iron fencing with tapered finials. The gate spans East Congress Street where it intersects Broadway, forming the main entrance to Congress Park, with a bronze plaque honoring Senator Brackett.

An architectural work of which Mr. Leavitt was very proud was Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, which opened in 1909. Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss, also a thoroughbred owner and frequent visitor to Saratoga Springs in the early years of the twentieth century, developed a firsthand appreciation of the Saratoga Club gardens and the park-like setting of the race track. He contracted with Charles Levitt to design a modern ballpark. In the sylvan countryside of Oakland, rather than the smoky congestion of downtown Pittsburgh, Mr. Leavitt created what would become the Steelers first home, and arranged an attractive arcade which encircled and supported the concrete and steel stands and landscaped the bucolic setting. Forbes Field served professional sports until 1970.

Charles W. Leavitt and his creative design ideas in landscape and architecture had a major impact on many national and global projects. An unfortunate bout with pneumonia in 1928 proved fatal for Mr. Leavitt at the age of 57. Fortunately, much of Mr. Leavitt’s past efforts are still very visible in Saratoga Springs today, yet he factored into the community in another nebulous, but far reaching way. In early March 1900 Mr. Leavitt filed a mechanic’s lien against the Empire City Race Track for his unpaid work. The owner, William H. Clark, had died unexpectedly at age 47 the previous month, and Mr. Leavitt’s claim began foreclosure actions against the new track. Mr. Clark had also heavily nominated his stable into future races, and due to Jockey Club rules (Rule #61) none of his extensive nomination funds could be returned to his widow. This unhappy ruling caused extensive conversation and a plan of action among horsemen. A clarion call went out in late October of 1900, when the second meeting was scheduled for the new Empire City track. A gathering was conducted by the sportsmen of New York for the benefit of Mary Sexton Clark, the widow of Mr. Clark, and their three young children. It was at this rallied assembly where Richard T. Wilson pitched his plan for a syndicate to buy Saratoga Race Course to William C. Whitney, a dynamic figure in national politics, finance and racing, and other racing men. The idea received immediate agreement, with the requisite funds for the Saratoga Racing Association venture quickly and successfully assembled, and the Spa track and grounds were purchased from Gottfried Walbaum in November 1900.

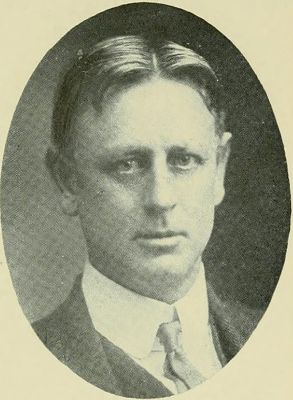

Portrait of Charles W. Leavitt Civil and Landscape Engineer from Empire State Notables by Hartwell Stafford, 1914. “For a landscape architect to take advantage of the opportunities open to him it is not enough to know something of design. Achievement in this field today demands far more…Vision and appreciation of beauty are of course essential, to be backed by a full understanding of architecture and of design…Yet with all of the knowledge that he can acquire he will be a success only when he works not as a creator, but as a guide in leading Nature to greater order and beauty.”

Richard Canfield, gambler and collector of paintings, sculpture, furniture, porcelains, rare editions of books and rugs, improved the Casino Building and added the Italian Garden, depicted in the New York Herald May 17, 1903.

Charles Leavitt designed the elliptical Paddock Building for the 1902 Saratoga season, and he also laid out the original Belmont Park, which opened in 1905 and had a very similar elliptical Paddock Building, only slightly larger. The Belmont Paddock was used until 1921, when the racing direction was revised from a clockwise direction (European or sometimes termed “Continental” style), to the present counter-clockwise direction. This made the Leavitt paddock superfluous, and it was used for parking before it was demolished. From the Official Souvenir Program Belmont Park May 4, 1905.

The Italian Garden attributed to Landscape Architect Charles W. Leavitt in ARCHITECTURE (magazine) Vol. VIII, No. 47 November 15, 1903,an early twentieth century publication of Forbes & Company.